Seabed Mining’s Ecological Dilemma — Tech Solutions and Conservation Challenges

- Jane Marsh

- Aug 22, 2025

- 7 min read

By Jane Marsh

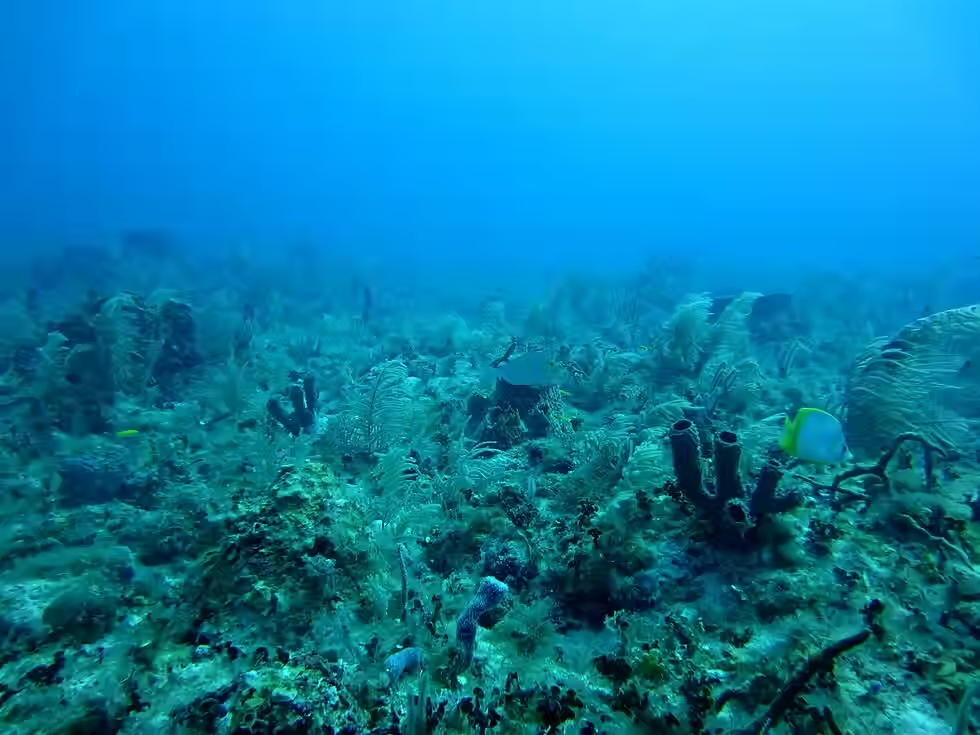

There are many headlines about what sits on the seafloor these days — metals that provide clean energy, robots that look like moon rovers, promises of “low-impact” mining. Scientists, island leaders and fishers also warn that the deep sea is not a blank slate. Standing between those stories, you want facts and a plan to protect the ocean you love. So let’s get straight to it.

The Scale and the Stakes

The ocean covers about 70% of the planet. Scientists estimate waters deeper than 200 meters — or the epipelagic zone — make up the lion’s share of habitable space for animal life on Earth. In other words, the deep ocean is not an empty basement — it’s most of the house.

Picture that vast living space and add another fact — the average ocean depth is about 3,682 meters. Standing on a beach, you can imagine a shelf of land that drops fast and keeps going. That scale should shape how you think about risk and responsibility.

Who Decides What Happens in “the Area?”

The International Seabed Authority oversees mineral activities on the seabed beyond any country’s borders, called “the Area.” That is a massive slice of the global ocean, placing a heavyweight responsibility on a small agency in Kingston, Jamaica. ISA members met for weeks in 2024 and still have not adopted a final Mining Code, so no one can legally start commercial mining in international waters yet.

Adding a plot twist, more countries have pressed the pause button. By mid-2024, at least 27 nations argued there isn’t enough evidence to start mining without risking irreversible harm, and they said so in the ISA meeting hall.

Meanwhile, the ISA issued 31 exploration contracts covering about 1.5 million square kilometers — mainly in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawai‘i and Mexico — but those contracts allow exploration only, not mining. Until members vote through the Mining Code, the lights stay red.

What the Newest Science Says About Damage

The facts suggest ocean disturbances travel farther and last longer than previously thought.

How far? A 2025 peer-reviewed study monitored a prototype collector test in the Pacific and detailed the sediment plume. Most of the mud kept hugging the seafloor, but researchers still detected changes up to several kilometers away. That is far enough to matter when you repeat passes, run multiple machines or add discharge plumes from surface ships.

How long? New field evidence shows tracks and ecological shifts from a 1979 mining test persisted more than four decades later. That time scale should make you pause. If one trial leaves marks for that long, what would an industrial season do?

Noise also complicates everything. Reviews in 2025 warn that commercial operations could add powerful, persistent sound into deep habitats and along migration routes for whales and other sound-sensitive species. Sound carries well in water, so a broader acoustic footprint extends past the mine site.

If you want a plain-language roundup, Smithsonian Magazine compiled the leading ecological concerns in mid-2025, from lost habitats to plume and noise risks, with links to primary studies. It’s a valuable reference to debunk the claim “We know enough.”

Why the Rush — and What’s Changed on Land?

The pitch for seabed mining rests on batteries and grids. Demand for critical minerals grew fast in 2023 and 2024 as electric vehicles and storage scaled — but markets moved, too.

The International Energy Agency reported significant year-over-year growth in storage, falling prices for several battery metals in 2023 and rapid manufacturing expansion. Battery chemistry is also shifting toward options that use less or no nickel and cobalt, like lithium iron phosphate. That doesn’t erase demand for copper, nickel or manganese, but it challenges “we must mine the deep” claims.

Though mining nodules will supposedly bring “energy justice” to rural communities, the reality looks more complicated. Rural and remote customers often sit at the ends of long lines, so they wait longer to get power back after major storms.

After Hurricane Helene in 2024, rural cooperatives warned of weeks-long restoration timelines in the hardest-hit areas. When recovery drags, outage fatigue grows and communities become more vulnerable. The energy quality problem demands resilience, not vague promises from the deep.

There is also a fairness gap on land. Rural regions often pay more for energy and get lower service quality because they sit far from central utilities — outages hit first and repairs take longer at the edges of service territories.

Tech That Can Measure, Reduce or Avoid Harm

It’s time for solutions, not hand-wringing. Technology won’t make the deep sea risk-free, but it can raise the bar for science and safeguards. Think of these as minimums if leaders ever consider moving beyond exploration.

It is unwise to green-light an industry and retroactively figure out how to monitor it. First, organizations should create transparent monitoring and strict thresholds, prove they genuinely work in the ocean, then decide whether the risk remains acceptable.

Real-Time Plume Tracking

Research teams combine acoustic Doppler current profilers, optical backscatter and camera systems to map plumes and redeposition in three dimensions during trials. A 2025 Nature Communications study confirmed that multisensor arrays can quantify how plumes sink, spread and settle, allowing regulators to set evidence-based limits.

Standardized eDNA Baselines

Environmental DNA sampling detects which species live in the water column and on the bottom without trawling. A 2023 review called for standardized, automated eDNA workflows to track biodiversity change, and deep-sea pilots in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone have already used eDNA to reveal far more species than nets alone. Pairing eDNA with visual surveys results in a sharper, cheaper baseline.

Independent Noise Monitoring

Companies can place hydrophones around lease blocks and set seasonal or dynamic closures when noise exceeds thresholds that could harm cetaceans and deep-diving mammals. Recent syntheses argue for broad acoustic setbacks because noise travels far. Building that information into contracts and public dashboards encourages anyone to audit.

Discharge Controls and Depth-Return Rules

If regulators ever allow processing at sea, they should require fine filtration and return of process water at depths that avoid mid-water ecosystems. Plume science from 2025 supports designing systems that keep particles near the seafloor and below sensitive layers, with live sensors verifying performance.

Open Data, Live Dashboards

Hiding data is the fastest way to lose trust. Agencies can require open, hourly streams for turbidity, noise and current profiles, plus rapid release of imagery and eDNA. The 2023 High Seas Treaty provides a path to set protected areas on the high seas and share monitoring data widely, letting everyone see what’s happening.

Governance That Keeps up With the Science

Targets keep moving. In 2024, the ISA elected a new secretary-general after a tense contest that spotlighted trust, transparency and conflicts of interest. The same session ended without a Mining Code, which means companies still need to wait. That stalemate reflects a deeper split — some states want a pause, while others push for a timetable. Until the ISA shows it can protect ecosystems at scale, the pause is a feature, not a bug.

Watch national moves, too. Norway approved opening parts of its continental shelf to seabed mining in January 2024, then faced legal and political pushback and signaled a slower path later that year. Scientists and coastal communities across the North Atlantic took note because regional choices influence global norms.

The “More Than Half the Ocean” Reality in Plain Words

Most of the international seabed — the part no nation owns — falls under the ISA’s watch. Think of a global common that spans vast distances and hosts little-known ecosystems. That is why the July 2024 count matters — 31 exploration deals exist, sponsored by a mix of countries from China to France, yet no state can start mining without a final vote.

The clock keeps ticking, but science keeps raising red flags.

What This Means on the Coast

You care about beaches, reefs, kelp beds and the offshore life that feeds them. You and your community also want clean energy that recovers quickly after storms. Your choices on shore can lower pressure offshore.

Support battery and grid strategies that cut seabed demand: Back chemistries and recycling programs that use less nickel or cobalt, push for design-for-recycling and ask local utilities to publish material footprints for storage procurements. IEA data shows rapid growth in storage and shifting metals markets — use that leverage.

Push your representatives to ratify and implement the High Seas Treaty: This agreement will unlock high-seas protected areas and environmental assessments beyond national waters. Ask for coastal-to-deep-sea corridors that consider migrating whales and pelagic fisheries.

Demand transparent pilots before any mining decision: No pilots, no permits. Require third-party monitoring, strong public reporting and community oversight panels that include Indigenous knowledge holders, fishers and local scientists.

Build real resilience for rural and coastal neighbors: Remote places wait longer for repairs after big storms. Ask regulators to prioritize hardened lines, microgrids and community storage along the coast so outages don’t cascade into health and safety crises.

The Bottom Line You Can Stand On

It’s possible to move quickly on clean energy and still be cautious in the deep ocean. The newest science reveals two truths — plumes and noise reach farther than one mining lane, and scars can last longer than some careers.

Governance is catching up, not leading. Until monitoring proves protection at scale, the wisest move is to champion tech that lowers mineral demand, push for ironclad rules and keep wild places wild.

Tide In, Not Tide Out

You don’t control the tides, but you can set the terms on your shore. Ask better questions. Demand better data. Back policies that protect the seafloor like it matters, because it does — for beaches you love, the climate you feel and the living space most of Earth’s animals call home.

Citations

National Geographic. All about the ocean. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/all-about-the-ocean/

NOAA. (2024, June 16) How deep is the ocean? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/oceandepth.html

IISD Earth Negotiations Bulletin (2024, Aug. 5) Summary report, 15 July – 2 August 2024. https://enb.iisd.org/international-seabed-authority-isa-council-29-2-summary

Environment.co. (2024, Aug. 27). Uncharted waters: Is deep-sea mining the future or an ecological disaster in the making? https://environment.co/deep-sea-mining/

Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. (2025, Mar. 10). Footprints of deep-sea mining. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/03/250305135139.htm

David Stanway. (2025, Mar. 27). Deep sea mining impacts still felt forty years on, study shows. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/deep-sea-mining-impacts-still-felt-forty-years-study-shows-2025-03-27/

Science Daily. (2025, June 24). Mining the deep could mute the songs of sperm whales. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/06/250624044317.htm

Amber X. Chen. (2025, July 18). As interest in deep-sea mining grows, scientists raise alarms about the possible ecological consequences. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/as-interest-in-deep-sea-mining-grows-scientists-raise-alarms-about-the-possible-ecological-consequences-180987009/

IEA. (2024). Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024/market-review

Robert Walton. (2024, Oct. 2). In areas hardest hit by Helene, rural cooperatives could need weeks to restore power. Utility Dive. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/hurricane-helene-rural-cooperatives-weeks-restore-power/728632/

Shipley Energy. The complete guide to choosing your energy provider. https://www.shipleyenergy.com/resources/energy/energy-deregulation/

Geomar. (2025). Footprints of deep-sea mining. https://www.geomar.de/en/news/article/spuren-auf-dem-meeresboden

Weiyi He, et al. (2023, June 2). Fish diversity monitoring using environmental DNA techniques in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/15/11/2123

Annika Hammerschlag. (2025, June 10). The UN Ocean Conference tries to turn promises into protection. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/un-oceans-conference-france-high-seas-treaty-9d46d372dc1f2d44bedbe41c84598bc8

Karen McVeigh. (2024, Dec. 2). Norway forced to pause plans to mine deep sea in Arctic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/dec/02/norway-deep-sea-mining-mine-arctic